Can we avoid climate apocalypse?

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Updated 1806 GMT (0206 HKT) November 27, 2015

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

And here's how the Houses of Parliament could look if temperatures rise by four degrees Celsius.

Hide Caption

8 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Parts of Mumbai could flood if temperatures rise by two degrees, according to the report.

Hide Caption

9 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Much more would be submerged in Mumbai, if temperatures rose by four degrees.

Hide Caption

10 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Here's Sydney with a rise of two degrees, according to Climate Central.

Hide Caption

11 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

At four degrees, water would start to lap at the stairs of the Opera House, the report says.

Hide Caption

12 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Here's Rio de Janeiro at two degrees warmer.

Hide Caption

13 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

And Rio again, if temperatures were to rise by four degrees.

Hide Caption

14 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

An artist's impression of how the Chinese city of Shanghai could look if temperatures rise by just two degrees Celsius. The following images show were provided by Climate Central, as part of report released November 8, 2015.

Hide Caption

1 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Shanghai, if temperatures were to rise by four degrees.

Hide Caption

2 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Durban, at two degrees warmer, according to Climate Central.

Hide Caption

3 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

And here's Durban, if temperatures were to rise by four degrees.

Hide Caption

4 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Here's how New York City might look if temperatures rise by two degrees Celsius.

Hide Caption

5 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Wall Street could go underwater, if temperatures rise as much as four degrees, according to Climate Central.

Hide Caption

6 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

London, at two degrees warmer.

Hide Caption

7 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

And here's how the Houses of Parliament could look if temperatures rise by four degrees Celsius.

Hide Caption

8 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Parts of Mumbai could flood if temperatures rise by two degrees, according to the report.

Hide Caption

9 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Much more would be submerged in Mumbai, if temperatures rose by four degrees.

Hide Caption

10 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Here's Sydney with a rise of two degrees, according to Climate Central.

Hide Caption

11 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

At four degrees, water would start to lap at the stairs of the Opera House, the report says.

Hide Caption

12 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Here's Rio de Janeiro at two degrees warmer.

Hide Caption

13 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

And Rio again, if temperatures were to rise by four degrees.

Hide Caption

14 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

An artist's impression of how the Chinese city of Shanghai could look if temperatures rise by just two degrees Celsius. The following images show were provided by Climate Central, as part of report released November 8, 2015.

Hide Caption

1 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Shanghai, if temperatures were to rise by four degrees.

Hide Caption

2 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Durban, at two degrees warmer, according to Climate Central.

Hide Caption

3 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

And here's Durban, if temperatures were to rise by four degrees.

Hide Caption

4 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Here's how New York City might look if temperatures rise by two degrees Celsius.

Hide Caption

5 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

Wall Street could go underwater, if temperatures rise as much as four degrees, according to Climate Central.

Hide Caption

6 of 14

14 photos: Submerged: What cities around the world will look like if temperatures keep rising

London, at two degrees warmer.

Hide Caption

7 of 14

Story highlights

- World leaders will meet in Paris on November 30 at the COP21 climate summit

- CNN Opinion invited experts to share their views on what the best solutions are

(CNN)It's probably the most important number you've never heard of: 2 degrees Celsius.

That's when climate change starts to get especially dangerous. Nearly every country in the world has agreed that 2 degrees of warming, measured as an increase in global average temperature since the Industrial Revolution, is too much to tolerate. Yet there's less agreement about how to achieve the ambitious goal of keeping the increase below that threshold, and how economies can switch quickly enough from dirty fuels like coal and oil to cleaner sources of energy like solar and wind.

World leaders will meet in Paris starting on November 30 to discuss all of this at the COP21 meeting of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Before that gets going, we invited authors, experts and activists to weigh in on the 2-degree target. What's at stake? And how can we actually get there?

Want to tackle the challenge? Try seeing how your views affect climate change with this calculator.

Mark Lynas: A catastrophic future

Call it the nightmare scenario. First, world leaders meeting in Paris this December fail to agree on a plan to cut back global greenhouse gas emissions. Renewables like solar power remain too expensive, and people stay irrationally scared of carbon-free nuclear. The world shifts back to burning coal.

Mark Lynas

Then we find out that the Earth's "climate sensitivity" -- how quickly and drastically the planet responds to carbon emissions -- is at the upper end of the range scientists predicted. Tipping points are crossed: Methane starts to belch out of the melting permafrost in huge quantities, and the ice sheets respond with what experts euphemistically call "nonlinear disintegration." Sea levels begin to shoot up.

In the latter part of this century we find the planet's temperature rise pushing not 2 degrees, as is the current internationally agreed maximum target, but 4, 5, even 6 degrees Celsius of warming. Large areas of the subtropics become biologically uninhabitable to humans: It's simply too hot to go outside. Food crops in breadbaskets wither in searing heatwaves, and extreme cyclones pummel coastal cities already under threat from the rising seas.

Could human civilization survive? We don't know -- but this nightmare scenario is surely a risk we should not take. We know how to make the shift away from fossil fuels. The time to act is now.

Mark Lynas, a British journalist, is the author of "Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet."

Kathy Kijiner: It should be 1.5 degrees

Scientists have warned that should the world exceed a global temperature increase of 2 degrees, catastrophe of the worst kind will hit. They have stated that 2 degrees is the safe zone.

Kathy Kijiner

However, in these same reports, scientists will add, almost as an afterthought, that at 2 degrees, the Marshall Islands -- my home -- and all low-lying atolls will be under water.

This is why our island leaders push for 1.5 degrees as the target, instead of 2 degrees. And yet 1.5 degrees continues to be a debate instead of the bottom line. The argument is that 2 degrees is achievable and a more realistic goal. But this comes at the expense of hundreds of atolls and thousands of lives.

If we prioritize 2 degrees as our target for global temperature, we are sentencing atoll nations to death. World leaders must not allow this to happen. I urge the world to hear our people's pleas and to save our islands.

Kathy Kijiner is a Marshall Islands environmental activist.

Van Jones: Embrace Obama's 'Clean Power Plan'

The age of fossil fuels helped America build its industrial might. But it came at a great cost, from children with asthma to global climate disruption.

We must keep global warming below a 2-degree increase or it will put our very society at risk. To get there, we need to stop the nonsense and embrace the future. In the wake of President Obama's recent decision on the Keystone XL pipeline, a new consensus is emerging that we must keep remaining fossil fuels in the ground.

Van Jones

Obama's "Clean Power Plan" is a good start, and it needs to be fully implemented. Americans need to take the Clean Power Plan and build on it with strong commitments to powering America with 50% clean energy by 2030. This will put us on a path to powering America with 100% clean energy by 2050 and send a signal to entrepreneurs and other nations.

Unfortunately, Republicans appear to be just as addicted to donations from fossil fuel interests as our nation is addicted to those fossil fuels. They are currently mounting an attack on the Environmental Protection Agency's common-sense plan to reduce global warming polluting from coal-fired power plants.

But there is hope. In every presidential debate, Republican nominees bemoan the lack of good American manufacturing jobs. At some point, they will catch on to the fact that those jobs exist -- in renewables. Today solar and wind employ more Americans than coal.

If we keep the focus on the future and well-paying, 21st-century jobs, we can overcome the fierce opposition of fossil fuel diehards and build a bipartisan consensus. Congress needs to stop burying its head in the tar sands. Our future is not down those holes. Our future is in clean energy and in the hands of the workers, inventors, entrepreneurs, and bold leaders who will lead the way.

Van Jones is president of Dream Corps and Rebuild the Dream, which promote innovative solutions for America's economy. He was President Barack Obama's green jobs adviser in 2009. A best-selling author, he is also founder of Green for All, a national organization working to build a green economy. Follow him on Twitter @VanJones68.

Fatih Birol: Is 2 degrees doable?

Since the first Conference of Parties in 1995, global greenhouse gas emissions have risen by more than 25% and the atmospheric concentration of these gases has marched steadily higher. As the largest source of global greenhouse gas emissions, actions in the energy sector can make or break efforts to achieve the world's agreed climate goal, while sustaining global economic growth and bringing modern energy to the billions who lack it today.

Fatih Birol

Is a dramatic transformation of the energy sector possible?

There are encouraging signs that the transition is already underway. Renewables have been gaining momentum -- collectively, they accounted for more than 40% of new power generation capacity worldwide in each of the last four years. And energy efficiency efforts have spread: The International Energy Agency's World Energy Outlook 2015estimates that the share of worldwide final energy consumption that is covered by energy efficiency regulations reached 27% in 2014, almost twice the level of 2005.

Pledges for Conference of Parties 21 in Paris will have a positive impact, but are consistent with an average global temperature increase of around 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100, falling short of the global goal of 2 degrees. COP21 must establish a clear long-term vision and certainty of action that will drive the right investments and accelerate the energy sector transition.

Fatih Birol is the executive director of the International Energy Agency.

Bjorn Lomborg: Ineffective responses so far

For 20 years, governments have tried to cut carbon emissions. The result has been two decades of failure with ever-increasing global emissions.

Governments have already revealed the carbon cuts they likely will commit to in Paris. All of these combined will reduce temperatures by a tiny 0.05 degrees Celsius (0.09 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2100. Yet the cost is likely to be more than $1 trillion annually.

Björn Lomborg

Carbon-cutting promises are ineffective and costly because solar and wind are far too expensive and inefficient to replace fossil fuels. We get a minuscule 0.4% of total global energy consumption from solar and wind, according to the International Energy Agency, and even by 2040 that will have reached only 2.2%.

We should end fossil fuel subsidies and invest much more in green energy research and development. This would be much cheaper and more effective than our current approach. We need to innovate the price of green energy down to where everyone wants to buy it. And we should acknowledge that wasting $1 trillion annually on minuscule temperature reductions is immoral and wasteful when there are major needs today -- from malaria to nutrition to family planning-- where small investments could achieve a great deal more.

Bjorn Lomborg, president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, is the author of "The Skeptical Environmentalist" (Cambridge Press, 2001) and "Cool It" (Knopf, 2007).

David Keith: Try solar geoengineering

One the most powerful options to counter climate change is solar geoengineering: an engineered increase in the Earth's reflectivity, resulting in cooler temperatures for the planet's surface. It might be done by injecting sulfate aerosols or even diamond dust into the stratosphere, where they would reflect sunlight just as do the droplets in a very thin cloud layer.

David Keith

It is not a substitute for cutting emissions -- it is a supplement. We can't keep using the atmosphere as a waste dump for carbon and expect to have good climate, no matter what we do to reflect away some sunlight.

The combination of emissions cuts and solar geoengineering could limit climate risks in ways that simply cannot be achieved by emissions cuts alone. It could, for example, allow the world to stay under the 2-degree mark.

But it makes no sense to start geoengineering today, since the uncertainties are far too large and the world lacks adequate mechanisms for governance.

We need research to sharpen our understanding on how to reduce the risks. Yet the U.S. has no research program on solar geoengineering because of a taboo based on the fear that it will lessen efforts to cut emissions. This is like refusing to develop chemotherapy for lung cancer out of fear that it will encourage smoking.

If we have no research program, then we give our children the gift of ignorance. If climate change is worse that we expect, then they will have to make decisions about geoengineering on that basis.

David Keith is the Gordon McKay professor of applied physics and professor of public policy at Harvard University. He is the author of "A Case for Climate Engineering."

Nancy Harris: Deforestation has to stop

All life depends on plants. Forests regulate climate and water cycles while providing the food, fiber, fuel, livelihoods and genetic resources upon which human societies depend.

Nancy Harris

In many tropical developing countries, greenhouse gas emission profiles are dominated not by fossil fuels, as for developed countries, but by deforestation. Here, it's a land management challenge. Every day, nearly 25,000 soccer fields of tropical forests are lost. Brazil's deforestation rates have dropped 70% since 2004, but loss is accelerating in other countries such as Indonesia, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Madagascar. How can they stop the deforestation that contributes 12% to 15% to human-caused emissions while still achieving their development goals?

It won't be easy, but Brazil has shown it's possible. As we wait for improved technologies in the energy and transportation sectors, reducing emissions from deforestation represents a low-cost and immediate option for limiting global warming to 2 degrees.

All countries can participate. Climate change impacts don't follow national borders, so it's in our collective interest to support the leadership of tropical countries in their transition away from a dependence on natural resource depletion and toward the preservation of forest landscapes, a critical element of current and future life on earth.

Nancy Harris is research manager of Global Forest Watch at World Resources Institute.

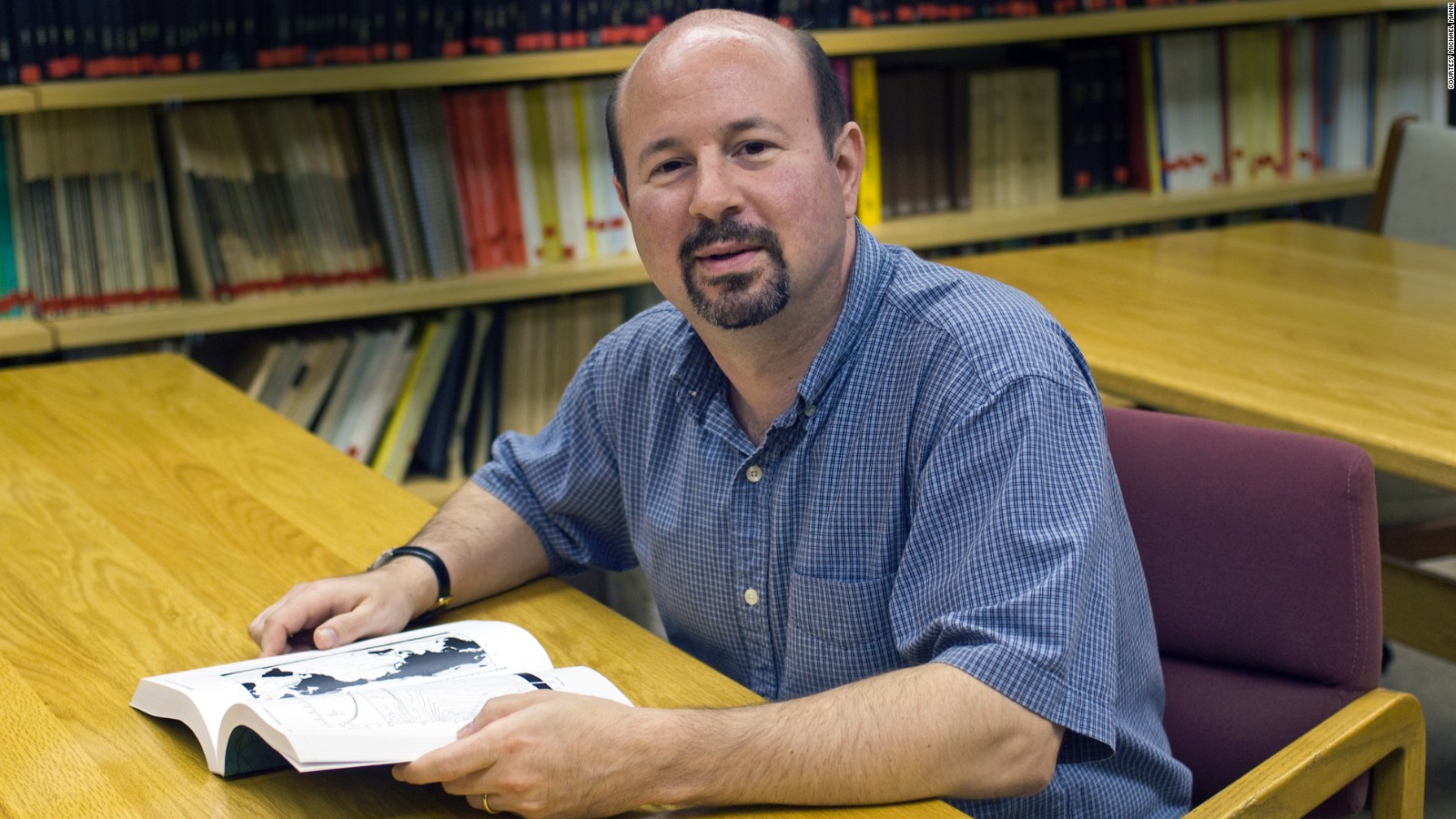

Michael Mann: Aim for renewable energy

We have seen significant commitments from the leading emitters -- the U.S., China, and now India -- to make substantial reductions in emissions. The collective pledges from all countries going to COP21 are already enough to get us halfway (3.5 degrees Celsius warming) from "business as usual" warming of 5 degrees to 2-degree stabilization. Through hard-nosed negotiations in Paris we ought to be able to get even closer.

Michael Mann

COP21 isn't the end-all in the battle to avert dangerous climate change. It's just the next step in an ongoing process.

In the years ahead, we must build on the progress we have seen in decarbonizing our economy. Such efforts would include market incentives to accelerate the transition already underway toward a renewable energy economy. We must also put a price on carbon to level the playing field in the energy marketplace so renewables can compete fairly. Such actionable goals provide a framework for making further progress in subsequent summits.

Michael Mann is distinguished professor of meteorology at Pennsylvania State University and author of "The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines" (with guest foreword by Bill Nye "The Science Guy").

John Reilly: Be more aggressive

Climate change is accelerating. Is 2 degrees the right goal? Can we live with 3 degrees? Island states will disappear because of sea level rise with 2 degrees or less warming.

John Reilly

Paleoclimate data show the sea level was 6 to 8 meters higher when polar temperatures were 4 degrees warmer. A 2-degree increase in global mean temperature would result in a 3- to 4-degree warming at the poles.

It may take centuries for this melting to occur, but it is not hard to imagine major portions of coastal cities like New York, London, Miami and Hong Kong under meters of ocean.

Unfortunately our ability to actually predict what will happen with global warming is poor, and so we have often already been surprised by heat waves and significant death, extreme flooding, rapid melt of sea ice, drought, ocean acidification and major dieback of forests from pest infestation.

Given our poor record of prediction, we can't adequately put a value on the climate impacts and the benefits of mitigation, and most estimates of these benefits are probably underestimates.

I am confident that sound economic measures -- a broad carbon price -- will unleash the creativity of people and industry to use existing solutions and invent new ones. The cost of mitigation may be a year to four years of growth over 100 years, but that will still leave us much wealthier.

Given the politics, there seems virtually no chance that we will mitigate "too much." We need to abate as aggressively as we can. If we miss 2 degrees and end up at 2.3 or 2.7, that is far better than continuing our current path and ending at 3, 4 or 5 degrees or more.

John Reilly, an economist, is co-director of the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change at the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research at MIT.

Wang Tao: Will China take serious action?

With an economy that's slowing down, China has legitimate concerns over the short-term impact of an energy transition that it pledges at the Paris climate conference. But that is no reason to back off.

Wang Tao

The determination of China in achieving a global climate goal is pretty clear, judging by all the joint climate change announcements it has made with the U.S., UK, Germany and France in the last couple of months.

What China needs to do is to reconcile the need to tackle climate problems with domestic reform of state-owned enterprises, especially the monopolies in the oil, gas and power sectors. In the long term, China has far more to gain by improving the efficiency of clean energy rather than relying on heavy (and dirty) industrialization.

It's time for President Xi Jinping to crack some real nuts in cleaning the air and mitigating climate change while growing the economy.

Wang Tao is a resident scholar in the Energy and Climate Program based at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy.

Katharine Hayhoe: Why Christians should care

To care about climate change, we don't have to be a certain type of person -- someone who already recycles, or bikes to work, or votes green. To care about climate change, all we need to be is a human living on this planet, a human who needs food, water and air to survive and a safe, healthy environment in which to thrive.

Katharine Hayhoe

If we're one of 2 billion Christians around the world, though, we have even more reason to care. The Bible reminds us that humans have been given responsibility to care for every living thing on the planet. It tells us that we are to be known for our love for others, particularly those who have less than we do.

Caring about climate change is not something that is foreign to Christian values, requiring a theology shift or a foreign belief. Caring about climate change is an opportunity to express our beliefs in a tangible, authentic way. We care about climate change because it impacts real people in serious and increasingly dangerous ways. And we know that the more carbon we produce, the more suffering there will be.

We need our science to tell us that climate is changing, and that our choices matter. We need our faith to make sure we make the right choice.

There isn't one best way to reach 2 degrees; it may not even be the best goal. It's like trying to make up a magic number of cigarettes someone can smoke and still be OK. There is no such number. But clearly, the fewer cigarettes we smoke and the sooner we are able to wean ourselves off our dirty and dangerous addiction, the better off we will be.

Katharine Hayhoe, founder and CEO of ATMOS Research, is associate professor in the Department of Political Science and director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University, part of the Department of Interior's South Central Climate Science Center.

Comments